Rachel has received two stem cell transplants to treat her acute myeloid leukaemia - ever since, she's been blogging about her journey.

She spoke to Billie in the Patient team about her experiences, and how her life and outlook has changed.

Tell me about when you first became unwell.

I had tonsillitis, and it just didn’t clear up after a week of antibiotics. So I went back to the GP. They ran a blood test to see if there was something underlying, and that kickstarted the diagnosis, really.

It took 17 working days (not that I was counting!) and the waiting was difficult, but I feel lucky. I’ve spoken to patients whose diagnosis was dragged out over a much longer period of time, as they weren’t offered a simple blood test.

My mother was a nurse, and I took A-level biology, so as soon as they mentioned ‘bone marrow’, I knew.

If it wasn’t some sort of strange anaemia, it was going to be blood cancer.

When was a bone marrow transplant discussed as a treatment option for you?

It was around the third cycle of chemo. They do tell you about the prospect of it at the very beginning, but it’s just a little warning, among all the other stuff you are taking in.

Did you have to wait a long time to find a donor? How was that?

No, I am super lucky to be common, apparently! I had four potential donors who were all 10/10 matches.

I‘ve met so many patients who don’t have donors. Especially people from ethnic minority backgrounds. They are told quite plainly by the hospital that their chance of finding a donor is limited. I didn’t have to face that.

I can’t imagine what that would be like to cope with, on top of everything else.

And how did you feel on transplant day?

A day of mixed emotions. You think stupid things like, ‘What if there is an accident and my stem cells spill out across the motorway?’ You worry all day. I kept asking the nurse every five minutes, ‘Are they here yet? Did they get enough?’

You’re excited, but on the other hand you feel so very indebted to somebody – which is overwhelming. You start to wonder about the donor; what are they like? In your mind, you make them a hero, and they are probably just a normal person who picks their nose!

But once they started the transfusion, it was much like all the other transfusions you’ve had so far. Because we think my donor’s Welsh, we played Tom Jones, and I wore a t-shirt with a sheep on it. (Laughter)

To make them feel at home?

Exactly. Although with my curly chemo hair, now I actually look a bit like Tom Jones, so perhaps I was too welcoming!

How did you find the isolation period?

That was hard. Especially after the second transplant; the chemo was really harsh, much stronger than the first.

You feel alright on the day of the transplant but the few days after it you get really low and you’re suffering all of the consequences of the treatment. Your throat is swollen and you can’t eat and you are sick. It’s horrible.

And you do sort of think, ‘Is this going to be worth it? Is it going to work?’ It’s very difficult, mentally.

However, looking back at it now, I did bounce back pretty quickly. It doesn’t feel like it at the time, as you don’t know how long it will last. I can only praise the hospital for getting me through it all.

What was it like going home?

Exciting, but a bit of an anti-climax. You are desperate to get home and cuddle your cats, but when you get home, the reality of the fact that you’ve got cancer kicks in. (Well, it did for me.)

Going out socially without your hair is something I found really difficult. You’re starting to wear turbans and wigs, and I know people don’t mean anything by it but they do stare.

When I looked in the mirror, I saw a cancer patient. I think these first four weeks were the hardest part.

How did it feel when you realised you were going to need another transplant?

That was about six weeks afterwards, when we realised my chimerism wasn’t as high as it needed to be.

When I think back, I took it quite well. I was on a bit of a mission, I’d had my chemo, transplant, lost my hair – this was just another thing I needed to do in order to survive.

We decided to go with another donor. The difficult thing was that I had to be completely clean of my first donor’s cells, and that took some time.

I found it difficult to manage other people’s expectations, too, when I didn’t have the answers myself. My 16-year-old nephew rang me, quite upset, and said, ‘Are you going to die?’

We are all going to die, but what do you say?

So that was a challenge: managing people while trying to stay positive when it had failed the first time. I found myself trying to convince myself and others, ‘No, this one is going to work!’

Who was your support network?

To be honest, the hospital and other patients more than friends and family, which doesn’t sound very nice.

At first I was a bit anxious talking to other patients, as obviously you do hear horror stories about treatment, and when you are first diagnosed that’s the last thing you want to hear, as it’s horrific enough already!

But over time, you do develop a macabre sense of humour and start to joke about all manner of horrible things. You can have a joke, that dark sense of humour between patients, which you can’t share with family.

Your loved ones take it deadly seriously, and it’s not that you aren’t taking it seriously; it’s just that sometimes if you don’t laugh about it, you’ll cry.

Friends and family are more difficult; again, it comes back to managing their feelings. My parents are elderly, and it’s very hard to tell your 80-year-old parents that you’ve got acute myeloid leukaemia. You wonder if their hearts can take it. So there was lots of staying positive for them.

A lot of people are baffled by the science of it all, too. By the time you get to the transplant you are a bit of an expert; you know what neutrophils are and what your platelets are meant to be, and people outside the world don’t understand the language. Talking to patients is good because you don’t have to explain everything; they just get it.

Obviously, the hospital also gives you access to psychologists, which I did take up for a bit. But I am the kind of person who just puts my head down and gets on with things.

Do you feel like your experiences with leukaemia have changed you? Have they sent you in a new direction?

Definitely. I can’t say I’m grateful for cancer; no one is. But it has made me a better person; it’s changed my outlook.

To be surrounded by people for months and months who are going through such difficult circumstances, some much worse off than me, it really puts life into perspective.

I remember this one time, when I was allowed out of the hospital, and I went to Pret to get a sandwich, and there was this woman next to me on the phone.

She was talking about her wedding – which is obviously important to her – but she was getting so worked up and angry about the shade of pink the flowers needed to be, because it wasn’t quite right, and I felt like dragging her into the hospital and saying:

‘Pink is pink.’

Sometimes we get so wound up by things that personally affect us that seem very important, but when you look outside your little bubble, they aren’t.

I’m more considerate, too and it’s made me think about doing more for other people. You don’t know when it could be you or your family that’s in need.

What was it like returning to the world of work?

Work’s been really supportive in allowing me time off to go to appointments, with lots of flexibility as they aren’t always easy to schedule.

I do still find it a very alien place. It’s very different from the hospital, where life-making decisions are made every day. Work just trundles along; people take three weeks to decide the name of a column in a spreadsheet. It feels trivial.

I was keen to get back to work to earn money, I’m a single person and I need a certain amount at the end of the month, but if I didn’t I’d be doing a different job. I would do something more oriented towards helping people.

You’ve recently moved to the Cotswolds. Can you tell me about your decision to move?

In my old house, when I was first diagnosed…it sounds funny, but I would look at myself and think, ‘What’s going on in there? Inside my body?’ I’d go to sleep and think, ‘Leukaemia is replicating inside me.’

So much happened to me in that house, and during my recovery when I came out of hospital, my home became a bit of a prison to me. I just lost the passion for it.

I wanted to put cancer behind me. I’ll always have to live with it; I’ve got someone else’s bone marrow inside me! But in that house and life, it defined me.

Also, the neighbours all know you’ve got cancer, and I just felt I wanted a fresh start.

I’d always loved the Cotswolds; it was a dream for retirement in the past, but cancer gives you courage. As someone previously terrified of needles I’d gone on to have bone marrow aspirations and I thought, ‘If I can do all that, I can sell my house.’

It was also a positive project to focus on during my recovery. Rather than just sitting on the sofa watching day time TV, waiting to go back to work I could achieve something. A few friends thought I was crazy! But I wanted to seize that courage. Worse things have happened to me, give it a go. If it doesn’t work out, that’s OK.

Can you tell me a bit about the late effects of your treatment? How are you managing?

I’ve got GvHD, mostly in my mouth, and I am getting pretty fed up of it. It is managed, and I have to remind myself that it’s a really positive thing as it reduces the chance of the leukaemia coming back.

I’m still on quite a heavy drug regime as a result, but I do feel that it’s a small price to pay. I am also showing signs of going through early menopause, which I’m not thrilled about. As I am getting back some ownership of my body, it’s about to start another unpredictable and unpleasant journey.

At least people don’t see it or know about it. When I returned to work, I moved office, so people don’t know I’ve had cancer unless I tell them. I’m grateful to have that choice.

Whereas a lot of friends say to me constantly, ‘You look so well’ and I know it sounds ungrateful, but it’s a constant reminder of cancer. I’m being treated differently.

And I don’t look well; I’m tired and my hair is horrific! They wouldn’t say this to me normally. And that’s all I want – for people to be normal with me. I wanted that when I was sick, too.

I hadn’t changed, I just had some dodgy bone marrow. I was still me.

What makes you happy?

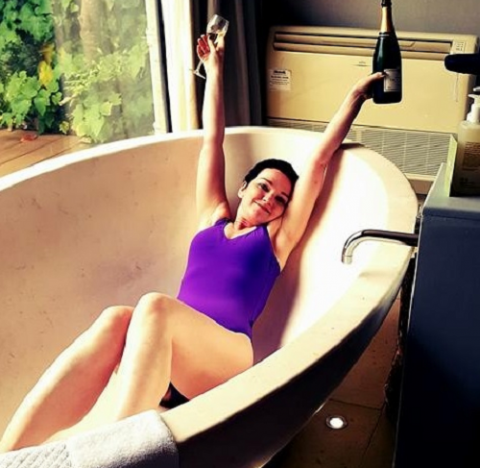

Being outdoors makes me happy. Being with animals, walking the dog, horse riding. Having a drink! Before I was sick I would cram a lot into my days; they were planned with military precision. Now I try not to plan everything.

If I’m off to a food market in the morning, I won’t plan my afternoon, so if I want to walk one mile, or ten miles, I can. Or I can spontaneously call a friend up to go to the cinema.

When you are sick, you have a very strict diet, and so I take real enjoyment in being able to eat a rare steak or have a glass of champagne. I have the green light for travel now, and I’m really excited about that, too.

I took these things for granted before. Being able to take back control of your life is very liberating.

After her transplant Rachel took on the Yorkshire Three Peaks Trek for Anthony Nolan raising over £4000 with her friends.

Do you think you’ll make contact with your donors one day?

I don’t know. I don’t think I’ll make contact with the first donor. It didn’t work, and that’s not their fault. I am still very grateful that they joined the register, and I don’t want them to be disappointed. What they did was amazing, and I wouldn’t want them to be put off doing it again for someone else.

The second one, he’s a hero to me and so to meet him in person would be a lot of pressure! It’s a hard one.

I’m so grateful to him. I don’t think words can ever really describe how much it means. He’s saved my life, but it’s the knock-on effect of all the other lives he’s touched.

Because of both of them, now I will hopefully get to outlive my elderly parents – something that means a lot to me. I will also get to spend more time with my nephew; I’m going to Portugal to meet his girlfriend now I can travel.

These are experiences that my donor has given me the chance to live. And that chance is an incredible gift.