A healthy gut

We have known for a long time that our digestive system is home to billions of tiny microbes that help us digest our food properly. We are even encouraged to look after them by drinking “pro-biotic” products that we are told will aid our digestion. But recent research has shown that bacteria also plays a key role in stem cell transplant recovery and the development of Graft vs Host Disease (GvHD) of the gut.

Last month members of the Anthony Nolan Patient Services team attended the British Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation’s (BSBMT) education day to hear about the latest medical research in all aspects of stem cell transplants. At this meeting, Professor Ernest Fuller from the University of Regensburg presented work on the microbiome and its role in stem cell transplant recovery.

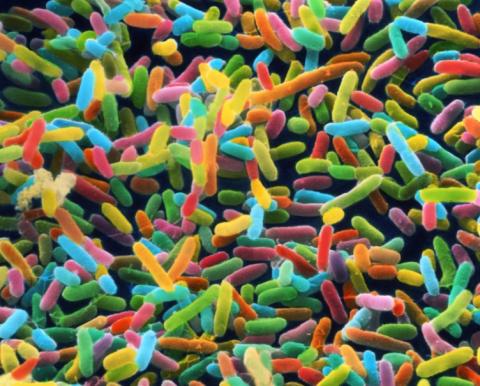

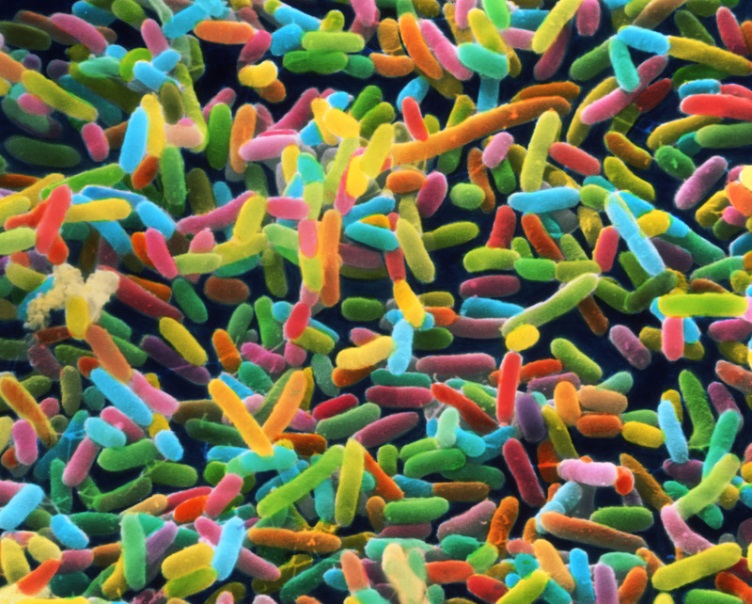

What is the microbiome? And why is it important?

The gut microbiome (or microbiotia) refers to all the microscopic organisms (bacteria) that reside in your digestive system. They are responsible for controlling millions of different chemical reactions that allow us to:

- release energy from food

- remove harmful toxins

- convert drug treatments into active forms.

However problems can develop when conditions within the gut allow one or two microbe strains to dominate and prevent the others from growing, just like weeds in a garden.

What did the research show?

The scientists have developed a test that allows the diversity (the number of different types) of gut bacteria to be measured by looking for the presence of a certain chemical. In the first study they looked to see if the levels of indoxyl sulphate (3-IS) in the urine of stem cell transplant recipients changed in the first few weeks after transplant. They found the chances of survival after one year were significantly higher in patients with more 3-IS, meaning they had a more diverse microbiome. In the second study, they showed that low levels of 3-IS were associated with the development of severe GvHD.

'The microbiome has also been the subject of two recent studies that focused on treating solid tumours, including lung and kidney cancer, with immunotherapy. Both studies showed that patients with more diverse microbiomes responded better to treatment.'

What does this mean for the future?

Microbiome diversity can be drastically reduced following antibiotic treatments, which could be a problem for people in recovery after a stem cell transplant. Antibiotic treatments are often essential during this time of compromised immunity in order to fight off infections – so it’s important to take them when needed. However work is now underway to identify antibiotics that are effective at fighting infections but still maintain a richer microbiome. Introducing the antibiotic Rifaximin has now been shown to improve patient survival, compared to standard post transplant treatment. It’s believed that this is due to Rifaximin’s ability to maintain microbiome diversity.

This work also opens the possibility of increasing microbiome diversity by introducing new cultures of bacteria, either after transplant or antibiotic treatment. However this will require more research into which combinations of microbes are important and how their growth is controlled, so that further symptoms of infection do not develop.

The microbiome and solid tumours

The microbiome has also been the subject of two recent studies that focused on treating solid tumours, including lung and kidney cancer, with immunotherapy. Both studies showed that patients with more diverse microbiomes responded better to treatment. This highlights the emerging importance of the microbiome in the development of new immunotherapy based treatments.

You can read more about this research on the BBC News website - bbc.co.uk/news/health-41848461

'The gut microbiome (or microbiotia) refers to all the microscopic organisms that reside in your digestive system. They are responsible for controlling millions of different chemical reactions'